When is a mini-budget not a mini-budget?

Chris Humphreys is tax partner with BHP.

I have to admit it’s taken me a few days to recover from the changes announced made by the Chancellor of the Exchequer last Friday, and to understand the impact of those changes.

Originally framed as a simple fiscal event, but renamed a mini-budget by the media, it has very quickly become clear that the measures announced represent the biggest economic gamble by government in my working lifetime and that there is nothing “simple” about this fiscal event or indeed “mini” about this budget.

It’s not the actual measures that cause me concern (although the abolition of the 45 pence in the pound additional rate tax band did come as a surprise) but just the audacity that a short, sharp growth plan funded by significant government debt will see the UK economy survive a minor recession and then recover from stagnant growth, high inflation and rising interest rates.

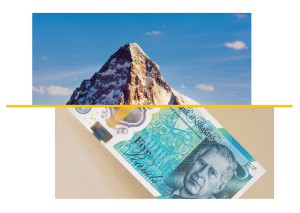

From what I can see the financial markets and many economists match my concerns with financial markets dropping, the pound under significant pressure and the Bank of England on notice to announce another significant hike in the UK base rate. Yesterday’s announcement by the IMF that government should rethink its strategy was also significant.

It feels very much like we’re watching one of those American hospital dramas where the patient has gone into cardiac arrest and the surgeon instructs the nurses to “stand clear” as he attempts to resuscitate the patient with the defibrillator paddles – and then we realise that we’re not watching it: we are the patient!

I’m reminded by my economist friends that we’ve been here before. Anthony Barber was Chancellor of the Exchequer under an Edward Heath government from 1970 to 1974. Mr Barber introduced his own Dash for Growth, or Barber Boom, when faced by slow growth, high inflation and rising energy costs, reducing both income tax and purchase tax at the time funded by an increase in government debt from £1bn to £4.5bn (it doesn’t seem much now, but it was a significant level of borrowing at the time).

The economy did pick up speed but only under enormous stress as inflation rose to 20% and unemployment rose. In addition, there was a three-day week to conserve energy and a secondary banking crisis which resulted in a collapse in the financial markets of the time. Unsurprisingly, Edward Heath was then voted out of office.

All sound familiar? Only time will tell whether the Kwarteng Konumdrum will be more successful than the Barber Boom but as I said earlier time is ticking and, “Stand Clear Nurse.”